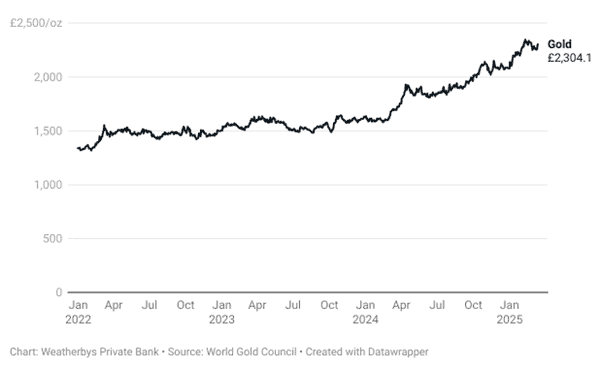

Gold prices soared

Metal set successive record highs in pound sterling and other currencies.

This led some wealthy UK investors to contemplate allocating money to the shiny asset. And indeed, it’s exactly that dynamic that makes gold a little unusual. For most of the things that people buy, whether ice creams, movie tickets or Savile Row suits, higher prices mean fewer items sold. People may spend more in aggregate on those goods, but they’ll usually purchase fewer units.

Price frenzy

With gold, the opposite happens. As prices rise, the increase in attention means that more people become enthralled by its virtues. Initially, that means more money flows in. Then prices rise more. And then more newspaper articles and web headlines follow. And a frenzy builds.

Bubbles in asset prices are as old as the Dutch love of tulips, and what they all have in common is the mess they make when they burst. The only thing more spectacular than the rally is the eventual crash.

In other words, manically rising prices are a terrible reason to buy any asset, unless you’re smart – or lucky – enough to get out before the top is reached, whenever that might be.

Soared, then crashed

After the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 prices rallied then crashed, and took a decade to recover.

Why gold rallies

That’s not to say there aren’t good reasons to own gold – as a currency hedge, it’s unrivalled; it offers shelter from inflation over cosmic time scales (though, less reliably over normal investment cycles) and it offers a fair amount of protection against generalised uncertainty. There’s also much to suggest that it acts as a volatility damping diversifier in well-structured portfolios.

What is important is knowing what drives gold prices in the long run, and what has caused the current conditions we’re seeing.

First, the general case: More often than not, price swings in the yellow metal are dictated by a combination of inflation-adjusted interest rates, and changes in the currency it’s measured in. Since gold pays no yield it tends to rise as interest rates fall, but on the other hand, as a hard asset, it tends to rise as inflation does. At the same time, the fact that gold’s value is measured in a currency, makes it clear that when the currency’s own value changes, that will impact the price of the metal. Change the unit on the ruler, and the measurement will also change.

But those factors do a poor job at explaining why prices are currently near records – inflation, after all, has dropped from post-pandemic peaks, governments around the world now pay more to borrow from investors, and the world of foreign exchange is relatively calm too.

Instead, what we’ve seen is that central banks, particularly those in emerging markets that tend to export much to the rest of the world, have been hoarding metal. India, China and Poland have all increased their holdings. And it makes sense, too, as much of their exports will be paid for in dollars, bringing gold’s currency-hedging qualities into play.

For the private investor, though, relying on the appetite of a handful of big, secretive buyers is problematic. Who’s to say when they’ll stop?

There’s another way

Luckily, there are better ways to gain exposure to gold prices. Gold miners, for instance, benefit from a rise in gold prices – and their performance tends to amplify the moves in the metal.

An example might be useful here. Let’s take a small gold miner that produces about 10,000 ounces of gold a year at a unit-cost of £1,500/oz. Let’s assume that when their operating decision was made, they forecast a long-term price of gold of £1,700/oz. That means they’re expecting a profit of roughly £200 × 10,000 ounces, or £2,000,000 per year. Instead, gold prices rally by 20%. Assuming costs stay the same, they’ll see the profit on each ounce by much more. In fact, those same ounces will more than double the profit to £5,400,000 per year.

And of course, those same miners would now have money to modernise their equipment, explore for new resources, and generally engage in activities that make them more profitable.

That’s the benefit of investing in human ingenuity over allocating money to an inert metal. Just like the folks in the old West who, when they saw a gold rush, decided to sell shovels.

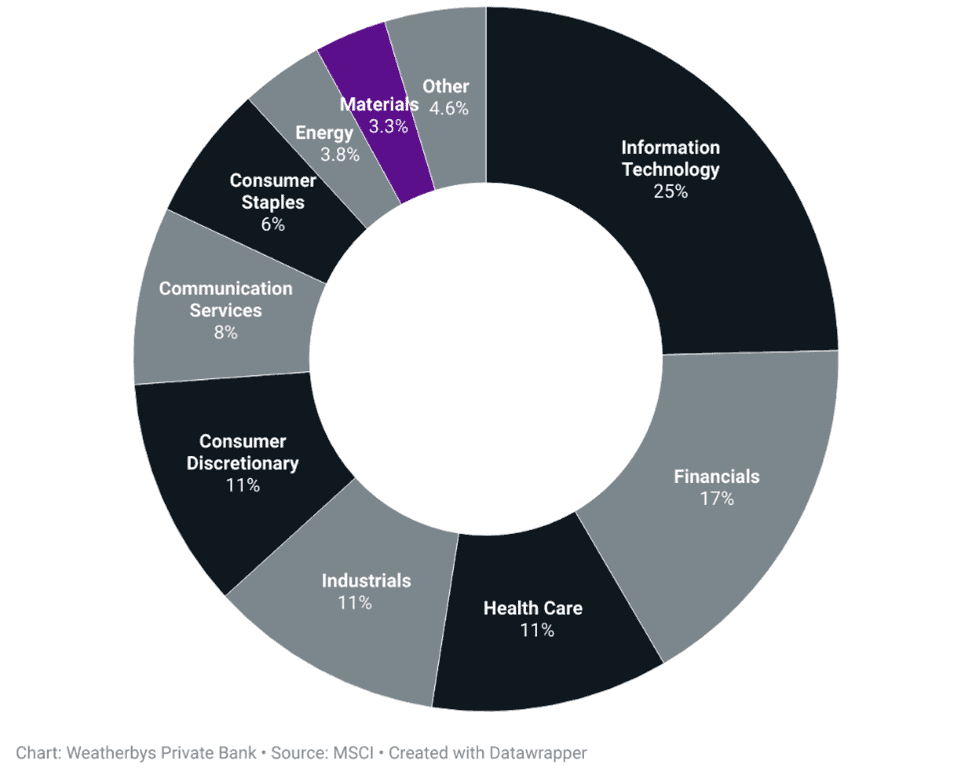

Investors in globally diversified portfolios, of course, will have exposure to gold miners, and indeed all manner of raw material producers, in the rough proportion that they’re represented in global equity markets, on a market-cap weighted basis.

Global diversification

Raw material companies, including miners, make up 3 per cent of market-weighted portfolios

That has the benefit, not only of backing human ingenuity, but also of diversifying and limiting the risk of mistiming a crash.

We think that’s smarter.

Important information

Capital at Risk: Investments can go up and down in value and you may not get back the full amount originally invested. The information contained in this article does not constitute financial advice and you should seek professional advice.