The 47th occupant of the Oval Office is not the first to come to terms with so-called bond vigilantes laying to waste finely laid plans. Soaring borrowing costs have cowed regimes throughout financial history. In 1983, Francois Mitterrand faced a market backlash leading to policy changes in France. Between 2008 and 2012, Greece, Italy and Spain saw borrowing costs soar, prompting a European debt crisis and forcing austerity measures. And let’s not forget the UK’s Liz Truss or an earlier International Monetary Fund bailout in the 1970s.

One of the most famous quotes in finance was uttered by Bill Clinton’s chief strategist, James Carville, who said: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope or as a 400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

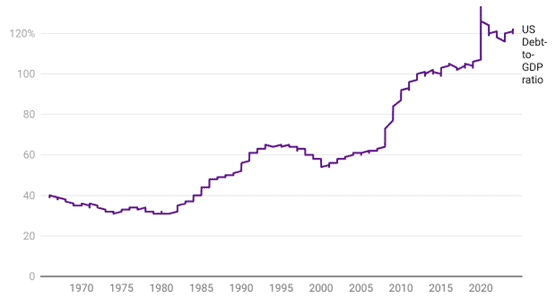

And just what is it that makes the bond market so powerful? Well, for starters, it dictates the cost of borrowing, and in modern developed economies, that’s a powerful force. The US, for instance, has a debt to gross domestic product ratio above 120%.

US debt has risen relative to the size of its economy

The US debt-to-GDP ratio is higher than in the past, but not as high as in 2020.

Chart: Weatherbys Private Bank | Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

When bond investors demand higher yields, the coupons the country pays on the vast majority of its outstanding debt does not change. But any new debt that’s issued will have to pay larger rewards, and in most cases, like a poorly managed credit card, the principle is simply rolled forward when each bond becomes due.

What makes this a particularly critical moment is that the US has about $9.2 trillion of debt set to mature in 2025, roughly a quarter of their total outstanding debt. This will generally be serviced by issuing new debt. But the catch is, much of this was issued between 2012 and 2022 when yields were closer to zero.

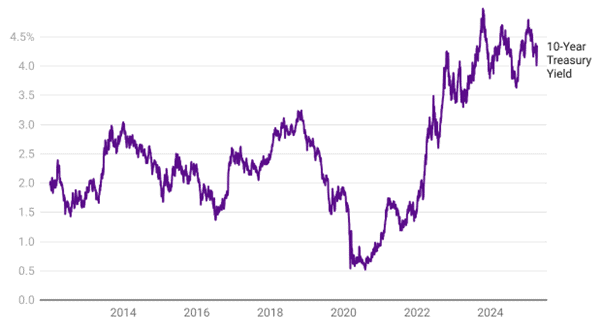

The average interest rate of US outstanding debt is about 2.5%. Now, of course, it will pay significantly more, about 4% across maturity dates.

US borrowing costs are now higher than in the recent past

The yield on 10-year Treasuries was at historically low levels in the previous decade

Chart: Weatherbys Private Bank | Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

In an emerging country, a debt-to-GDP ratio as high as that of the US would be enough to trigger disruption on the scale of the Asian financial crisis that started in Thailand in 1997 and spread to Indonesia, South Korea and Malaysia, ending in bailouts from the IMF.

But the US is not an emerging market nation. It is the issuer of the world’s reserve currency. This makes a debt default less likely. Most of its bonds are denominated in its own currency, unlike emerging nations that often have to borrow in currencies convenient for borrowers.

That has two implications. First, if it struggles to pay its debt, it can simply print more money. And second, over time, it can deflate its currency, making the debt burden more manageable.

Yet even the US president pays attention when his country must refinance so much of its outstanding debt in a matter of months.

A further complication is that Trump’s policies have conflicting implications for the economy and monetary policy. Tariffs tend to boost inflation as people pay higher prices for imported goods. When central bankers see rising prices, they generally want to raise interest rates. But tariffs also tend to slow economic growth, and policy makers usually cut interest rates when a recession looks likely. Relatedly, bond investors would like to own long-duration bonds when slowing growth force rates lower, and they want to be in other investments when inflation speeds up.

The sum of those conflicting factors is that traders have less confidence in allocating money to bond markets.

At the start of this week, wild gyrations erupted in US Treasury market with ten-year yields fluctuating in a 35-basis point range on Monday. Longer-dated yields climbed relative to shorter-dated ones, steepening the curve. Differential between swaps and yields blew out, showing trouble in derivative markets. Trump caved shortly after, cutting tariffs on most countries except China, and the bond markets calmed.

The bond market has long been a source of diversification for investors, and it’s comforting to note that particularly the shorter-date bonds continued to act as a source of stability and a haven asset. That’s particularly important for investors in the least risky portfolios, such as Weatherbys Global Tracker Portfolios 1 and 2, which have been positioned to benefit from the relative lack of variability of returns at the shorter end of curves.

Important information

Capital at risk. Investments can go up and down in value and you may not get back the full amount originally invested.

Past Performance. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.